Nuclear Chess: Game Theory lessons from Oppenheimer

Game theory analysis of incentives and outcomes in a post-nuclear world inspired from the movie Oppenheimer

Oppenheimer was a great watch. It had everything; mind-numbing science, eye-raising shots, soul-stirring scores. It kept me hooked throughout all 180 minutes. In fact, some moments took me back to my game theory class in college.

While the movie did cover a lot on the shadowy realm of international relations, it did not have much to say about strategy and game theory. I was trying hard to fit the facts of the movie into some of the concepts that I had learnt in the class. Nolan’s masterpiece and our complex nuclear politics can hardly be simplified into a 2x2 game theory matrix, but I try.

In the intermission, I mobilised some of these thoughts into words.

Before we begin, here is a short note on game theory if you are unfamiliar: Game theory involves creating theoretical frameworks to understand and predict how entities make decisions in situations where their choices depend on the actions of others.

It is important to look at conflict using game theory as decisions that countries make during war are not one-sided. The chances of retaliation are real and so they must make the decision anticipating the enemy’s response.

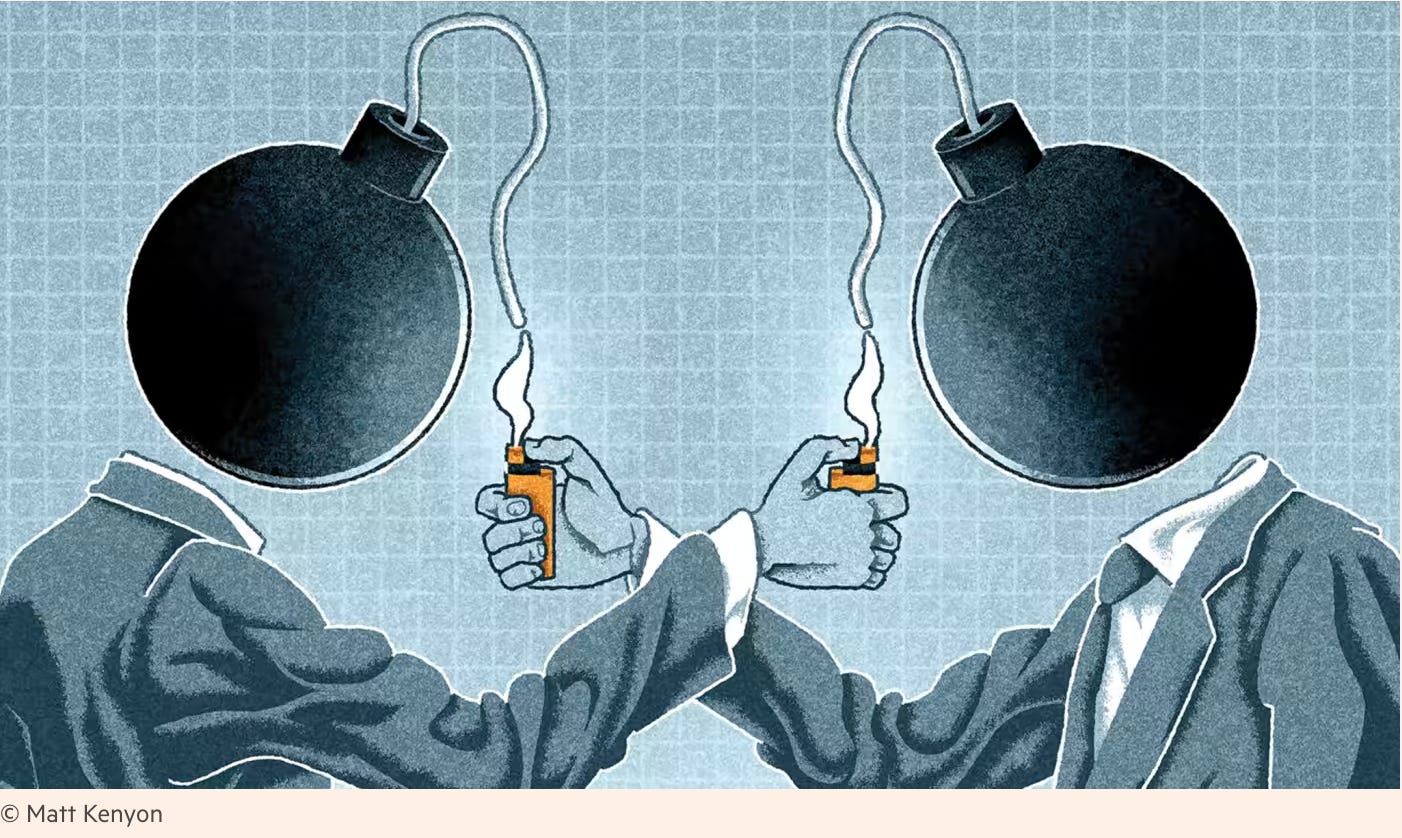

So, in today’s newsletter we will be exploring the game theory of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD). While MAD sounds threatening, you’d find its outcome is rather relieving. We will also be looking at the concept of the arms race and how it spills over from MAD.

Mutually Assured Destruction:

The doctrine of MAD argues that the mutual existence of these weapons of mass destruction discourages countries from using them.

For example:

Scenario 1: Country A has an atomic bomb, but country B does not. This makes country A the one with an upper hand and can leverage country B into submission by using them or threatening to use them. There is a risk for escalation by country A as it has an incentive to use it.

Scenario 2: Country B has an atomic bomb, but country A does not. Now, country B has the upper hand and can threaten country A. So, there is also a risk of escalation by country B.

Scenario 3: Both Country A & B have nuclear weapons. Now this is where it gets interesting. Neither country has an incentive to escalate as they would know the other country will have the option to retaliate causing widespread destruction in their country. This chain of attack and counterattack would continue until they have run out of weapons or people for that matter. So, if any country uses a weapon of mass destruction, it will eventually lead to mutual destruction. Knowing this is disincentive for countries to use highly catastrophic weapons. It’s as if any use of bombs is deemed too risky because of the inevitable outcome of mutual annihilation. A not-so-dismal outcome from the dismal science, huh!

Professor Falken, a fictional character in the movie War Games described MAD as:

“A strange game. The only winning move is not to play.”

The Arms Race

However, maintaining scenario 3 (Mutually Assured Destruction) is an expensive affair. Almost all countries want the bigger stick in the fight, which incentivises its opposing country to match it. This unleashes a competitive process in which countries constantly upgrade their arsenal in order to one-up the enemy or atleast catch-up with their progress. This leads to the spiralling escalation of defence expenditure - the Arms Race. We saw this happen in the movie; when the Americans learned that the soviet union had tested its first atomic bomb, they began discussing the feasibility of a Hydrogen Bomb. The H-bomb was said to be 1000 times more destructive.

This chart clearly shows the proliferation of nuclear weapons up until the end of the cold war when countries decided to reduce their stockpiles.

There were significant efforts to de-escalate risk by introducing international programs like non-proliferation treaties, and so you can see the significant drop post Cold War.

It is crucial to note that game theory is only a framework with really tight and unreal assumptions. A framework that points us in the right direction, but a theoretical framework nonetheless. Nothing seems more apt to end this essay than the words of Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer ‘Theory will only take you so far.’

Here is some classic twitter humour

Job Listings:

Data Journalism Intern: IndiaSpend is looking for a Data Journalism Intern

Research Assistant (Economics): Professor Ram Singh, Delhi School of Public Policy and Governance is looking for a research assistant for the Opinion Section of an economic daily

Research Assistant (Psychology): Professor Aneesh Varrier is looking for a research assistant in psychology at Christ University

Good articulation! Well, even I feel the logic of deterrence is always at work in global politics.

Great read and well explained!